This article first appeared on psychologytoday.com on 28 June 2022.

The recipe for living and working successfully across cultures calls for many ingredients. One of them is a set of capabilities under the umbrella of Cultural Intelligence (CQ). Regarded as an essential intelligence for the 21st century, CQ is a complex and dynamic construct.

For decades, psychologist Soon Ang — one of the first scholars to introduce the concept of CQ — has been researching what makes certain individuals and organizations more proficient in maneuvering the novelty and discrepancy inherent in cross-cultural encounters. After all, as Ang noticed during her extensive travels, it wasn’t only our values that varied across the world — even the values we assigned to our lives were far from identical. The reality of our vast differences co-exists with the still vaster potential of human intelligences. Drawing upon our social, emotional and academic faculties, CQ allows us to find solutions, adapt to our environments and learn from each other.

4 Components of CQ

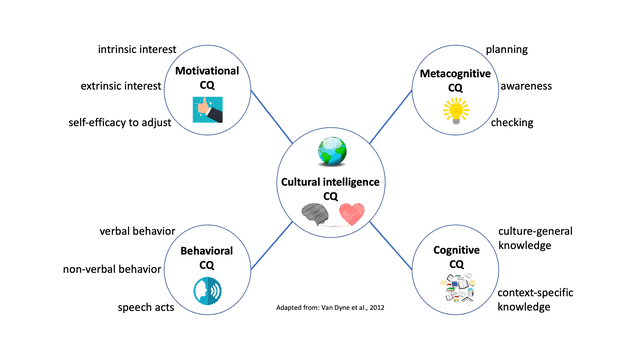

Ang and her colleagues have identified 4 key components of CQ and their subdivisions. Below is a summary of their findings (Van Dyne et al., 2012).

1. Motivational CQ

Motivational CQ refers to the ability to “direct attention and energy toward learning about and functioning” in cross-cultural situations. Individuals with high motivational CQ tend to be drawn to intercultural experiences and have the confidence to manage them successfully.

- Intrinsic interest: The satisfaction and value that interactions with others from different cultural backgrounds bring. People with high intrinsic interest tend to gain “self-generated benefits” from their cross-cultural experiences.

- Extrinsic interest: Being motivated by the tangible, variable-dependent benefits of cross-cultural experiences, including promotions and new opportunities. Organizations frequently use these extrinsic rewards as incentives for employees on international assignments.

- Self-efficacy to adjust: Confidence in the ability to engage, interact and work across cultures.

2. Cognitive CQ

Cognitive CQ describes the wide scope of general knowledge individuals hold about cultures. Here, as Ang points out, Google can be our best friend. Two kinds of knowledge contribute to the success of cross-cultural experiences: culture-general and context-specific knowledge.

- Culture-general knowledge: Declarative knowledge about the main elements that make up cultures (value systems, political, historical and philosophical traditions, social and communication norms, insight into local languages).

- Context-specific knowledge: “Insider understanding” of the norms and rules of behavior among various demographic subcultures within a culture (age, gender, occupation).

3. Metacognitive CQ

Metacognitive CQ refers to a person’s “mental capability to acquire and evaluate cultural knowledge.” Individuals with high metacognitive CQ have heightened awareness of self, other and situation, monitoring and adjusting their inferences in response to input from intercultural experiences. Metacognitive CQ involves 3 processes that are activated before, during and after interactions:

- Planning: Preparation before cross-cultural encounters. Individuals reflect on their goals and objectives prior to the interaction and anticipate possible outcomes by considering the cultural perspective of their interlocutors.

- Awareness: Being conscious in real-time of culture’s influence on thinking, feeling, and behavior.

- Checking: Re-calibration of expectations, assumptions and beliefs that occurs during or after cross-cultural interactions. As new information is learned, the individual adapts their mental maps accordingly.

4. Behavioral CQ

Behavioral CQ is the capability to put knowledge into practice and to demonstrate an extensive range of culturally appropriate verbal and non-verbal behaviors. Individuals with high behavioral CQ can appear as more effective and respectful communicators, thanks to their ability to adjust the content, structure and style of their communication.

- Verbal behavior: Capacity to express oneself linguistically. This might include tailoring one’s tone of voice or the speed, warmth, formality of speech to appropriate cultural standards. Knowing when and how to use silences during conversations, as well as the etiquette surrounding taking turns are all implicated in linguistic rules of communication.

- Non-verbal behavior: Ability to express oneself through culturally appropriate non-verbal means (gestures, facial expressions), as well as to read others’ body language.

- Speech acts: Knowledge about the culture-specific nuances of expressing apologies, gratitude, warnings and refusals.

The How of CQ

According to Ang, the belief that cross-cultural exposure will automatically yield CQ is a common misconception. Employers, for example, often consider the travel history of their employees when assessing potential candidates for global assignments. Empirical research, however, suggests a more complicated picture. Firstly, as Ang points out, people engage with local cultures to varying degrees. The anxiety and uncertainty that frequently accompanies cross-cultural experiences might prompt some to stay close to their comfort zones, even while being far from home. This might mean sticking to familiar types of people, foods and situations, rather than venturing into a deeper engagement with the new culture.

Secondly, there are various moderators involved in translating contact into CQ. According to the experiential learning theory, for example, having a cross-cultural experience is only the first step of a four-step learning process required for developing CQ. The other three steps involve critically reflecting on the experiences, turning reflections into “more general theories to guide future behavior,” and testing out the new behaviors to evaluate their effectiveness (Ang, 2021).

Training CQ

Researchers have devised various interventions to train the four components of CQ. For example, to train metacognitive CQ, Ang and her colleagues use intercultural situational judgment tests (SJTs). The premise of these trainings resembles theory of mind exercises. After watching short video clips depicting various cross-cultural situations, participants are asked questions to gauge their insights into the characters’ minds (“What are the characters in the clip thinking and feeling? What is their intention?”). Ang has found that people who can’t accurately “diagnose” cross-cultural situations, tend to hold rigidly ethnocentric views that prevent them from seeing things from other perspectives.

The Why of CQ

For those living and working in intercultural contexts, CQ offers obvious benefits, including cross-cultural adjustment, cross-cultural negotiating proficiency and global leadership. If at the heart of human intelligence is the ability to solve problems, then, like with other kinds of intelligences, CQ can serve us in finding solutions in unexpected ways. David Livermore, a leading expert in CQ, offers three possibilities.

1. CQ as a catalyst of innovation

The link between diversity and innovation is not as straightforward as commonly presumed. In fact, research shows that when it comes to innovative ideas, homogenous teams often outperform diverse teams. The reason, according to Livermore, is because it’s easier to work with people who think and communicate like us. CQ appears to be the catalyst that facilitates innovation from the wealth of perspectives that diverse teams foster. Livermore calls CQ a multiplying factor. “When diversity is combined with CQ, it does, indeed, lead to innovation. In fact, diverse teams with high CQ produce over three times more innovative ideas than homogeneous teams.”

2. CQ as a common language for addressing issues of diversity

From working with global organizations, Livermore noticed that often, US companies receive feedback from their international offices about their D&I initiatives being too US-centric (e.g., focused on issues of race). CQ, according to Livermore, “goes beyond awareness of differences to developing the skills needed to address diversity.” Thus, CQ allows companies to find “a shared approach while allowing each region to address the specific areas of discrimination and bias in their respective regions.”

3. CQ as a bridge between differences, near and far

The benefits of CQ are not limited to those whose lives traverse cultural borders. As Livermore notes, “the competencies that make up CQ are ideally suited to help us overcome polarization with individuals closer to home who have wildly different perspectives than us.” In fact, according to Livermore, CQ might even teach us how to loosen our insistence on being right and use our differences as an impetus. “By learning to apply the same curiosity, understanding, and mindfulness to a family member or friend with a different perspective as what we do when interacting with someone from the other side of the world, we can find common ground and discover solutions to some of our challenges.”

A note on harnessing our differences

In a way, CQ points to the potential of navigating our differences more skillfully. As Ang notes, in any given interaction, our differences can be seen as enriching or threatening. For example, the more diverse people are, the greater the potential to learn from each other. However, besides providing opportunities to exchange information, our interactions often turn to exercises in social categorization. We attend to available cues and assess our standing in our shared space. “Is it a you and a me, or is it a we? Do I feel like I belong, or do I feel out of place?” According to Ang, it is this clash between cognition and social identity that makes harnessing our differences so complex. Her advice: in your interactions with others, before diving into information exchange, establish a felt sense of belonging together first. Connect to our common humanity — helpful instructions for interpersonal relations of all designs, at home or abroad.

Many thanks to Dr. Soon Ang and Dr. David Livermore for their time and insights. Professor Ang is Distinguished University Professor at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore (NTU, Singapore). She pioneered the concept of cultural intelligence. David Livermore is an author, a social scientist researching cultural intelligence and global leadership, and the founder of the Cultural Intelligence Center in East Lansing, Michigan.